Ashling Murphy, Jill Meagher, can apps counter harassment of women?

On 10 January, the British Government endorsed an app for women's safety. The app allows women to broadcast their movements to somebody else. Similar apps already exist in Saudi Arabia, keeping husbands and fathers in control of womens' lives. Inside the UK app, we might find binary code copied directly from the Saudi app, sugar coated to look like a tool of empowerment.

Two days later and a woman in Ireland, Ashling Murphy, was murdered in broad daylight. The Irish press was quick to compare this with the murder of Sarah Everard in London but the tragedy that came to my mind was the 2012 murder of Jill Meagher. Meagher emigrated from Ireland to Melbourne, much like my own mother. Meagher was abducted in a main road and shopping district where I used to go almost every day. I was born in the same district.

Murphy's death is also a good moment to contemplate the actions of Brittany Higgins, the woman who stood up to the Australian government after they covered up her rape on the defence minister's sofa. It appears Murphy demonstrated similar courage and strength: after strangling her to death, the prime suspect checked himself into hospital. When Higgins called out both the rape and cover-up, Australia's defence minister checked in to hospital.

Higgins waived her anonymity while it appears Murphy fought with all she had. Both of these women have made a huge sacrifice that will make other women safer.

|

|

Meagher's murder received blanket news coverage in Australia, partly because Meagher had been employed in the media. It quickly led to debate about the phenomena of the single white female victim. Some commentators pointed out that teenage migrants from Sudan and Ethiopia had disappeared without any public interest in their plight. This phenomena doesn't diminish victims like Meagher and Murphy yet it is important to remember their deaths represent a wider problem.

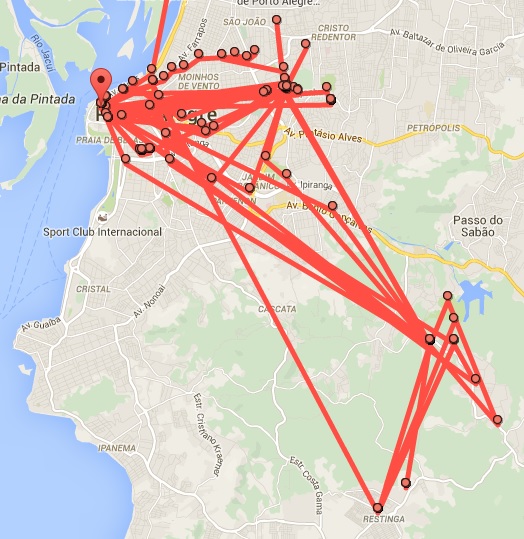

Irish Police (Garda Síochána) may have already examined data from mobile phone towers to discover the suspect's movements. This data may reveal whether it was a random attack or whether he had been following women every day, making notes about their behavior, trying to anticipate their movements. Ironically, Ireland's tech sector includes large offices for Facebook and Google, where a predominantly male workforce creates algorithms to monitor and predict the decisions and movements of their targets. Frances Haugen's brave testimony before the US Congress confirms these men actively make choices that hurt women and children.

Public leaders have been quick to proclaim new policies to protect women. Personally, I feel that cultural change may do more. For example, if a tech monopoly uses coercive and deceptive practices to trap people in their service, we need to be in the habit of equating that with the men who use substances or deception to control women.

One of my female interns in the Outreachy program wrote about a sponsor, Google, stalking her. In response, all she received were threats and insults. Google set about discrediting Renata and I just as Facebook has tried to discredit Frances Haugen. The Google employees claim they are the victims of harassment and abuse: how can they equate themselves with the trauma experienced by women like Ashling, Jill and Brittany?