Mayday: Optus emergency calling crisis

Customers of Optus were unable to make emergency calls for nine hours on Thursday, 18 September 2025.

It is not clear if the fault lies in the routing system or in the call center where the calls are handled.

It is not clear if they are talking about mobiles or landlines or both.

If mobile customers were in scope for the outage then it raises serious concerns about the ability of mobile handsets to route emergency calls to alternative networks.

Context and history

Australia deregulated telecoms in the early 1990s. Optus was the first company given the opportunity to compete with the incumbent state monopoly in 1991. They were backed by the UK's Cable & Wireless and the US company BellSouth. Therefore, they have a lot of experience in the Australian market.

As a teenager, I was the youngest person to pass the amateur radio exam in my city. Amateur radio licensing is administered by ACMA, the same authority who regulates phone companies. The amateur radio exam requires all licensed amateurs to be capable of transmitting emergency messages. As part of WICEN, I completed additional training and practice at community events such as the Southern 80 ski race and the Red Cross Murray River Canoe Marathon. Given the remote nature of these events, radio amateurs become very aware of the level of responsibility we have to keep the community safe. The Southern 80, in particular, has had numerous deaths over the years.

When I first started consulting on IP-based telephony networks in the UK, the market was highly de-regulated. Officials from the Home Office were very concerned about the possibility that people using IP telephones may not be able to make emergency calls. Given the UK Government is keen on deregulation and competition, they couldn't ban IP telephony so the authorities dedicated resources to engaging with our industry and running regular meetings to discuss the risks and solutions.

The simple fact is many of us in the industry have had meaningful discussions and meaningful experience over many years. Situations like this do not come as a total surprise to the telecoms companies. With the right people and protocols, it could have been handled better.

In 2013, news stories simultaneously appeared about emergency call centers failing in Melbourne, Australia and Detroit, USA. I made a note of that on my blog. Were both call centers running the same software or did they have a common dependency that nobody else noticed at the time?

In 2023, the entire Optus network, including Internet, mobile and landline services failed between 04:05 and 13:00 AEDT. This total failure impacted many other services, including payment systems in shops, security alarms and monitoring for people with high risk medical conditions. Emergency calls were not possible during the outage.

After the 2023 incident, there were high level discussions between state officials, emergency services and the managers of the telecoms companies. Protocols were agreed for handling a similar problem if it ever happened again.

On 18 September 2025, in the early hours of the morning, Optus apparently made a firewall change and failed to realize the change had impacted their ability to handle emergency calls.

At approximately 9am some customers were able to contact the regular customer support number and report an outage in emergency calling.

Optus alleges they have records of over 600 failed emergency calls. They began making welfare checks on the callers by trying to return the calls some time in the afternoon.

The fact that Optus was making the welfare checks suggests that the emergency call center is managed by Optus too. It is not clear if the same call center is also subcontracted to other networks.

The problem was fixed late in the afternoon.

The police and state authorities were only informed after the problem was fixed and after attempts were already under way to make welfare checks.

The communications regulator, ACMA, was only notified after the outage.

The authorities were initially told that only 10 calls were missed.

On 19 September, Friday, authorities were told 100 calls had been missed.

Another twenty minutes after that, Optus revealed a total of 600 calls had been missed. Nobody is sure if this is the real number.

On 19 September, the boss of Optus revealed three people had died.

Subsequent reports have speculated that one of those deaths would have happened anyway even if an emergency call was made. The coroner will have to decide if the other two deaths were due to the failure of the emergency call center connectivity.

Resilience of emergency call centers

Multiple call centers are usually established in different parts of the city or state so that if one call center has a catastrophic failure, the other centers can handle the calls.

Each call center ideally has independent connections to each telephone company.

When the British Telecom (BT) telephone exchange caught fire in Manchester, people discovered that the call centers didn't have direct radio contact with ambulances. The call center was relying on a line from BT to join the radio transmitters to the call center.

The call centers should be able to detect if a particular phone company stops sending calls to them. Many call centers already have real-time statistical analysis of calling patterns to help them identify problems that might cost them lost sales. It would be nice to see them using the same statistical analysis tools to detect an absence of emergency calls.

However, call center management is often outsourced. It is not clear if the call centers themselves are also managed by Optus or some other company.

Bubble-wrapped people avoiding critical commentary

Why did it take so long for Optus to inform state authorities and police that there was an outage?

To understand that, we need to look at the problems in Debian and other free software organizations.

Debian spent over $120,000 on legal fees to avoid critical commentary. This shows the extent to which people will go out of their way to avoid hearing an inconvenient truth about their organization.

I have no knowledge of the internal problems at Optus. But it would be reasonable to ask if people were afraid to tell their managers about the problem because they were afraid of criticism. Were the managers afraid to inform police commanders out of a similar fear of criticism?

After Debian spent all their money on legal fees to avoid critical feedback, volunteers were asked to use their own money to pay for the day trip at DebConf23. Abraham Raji didn't pay anything, he was left alone to swim unsupervised and he drowned.

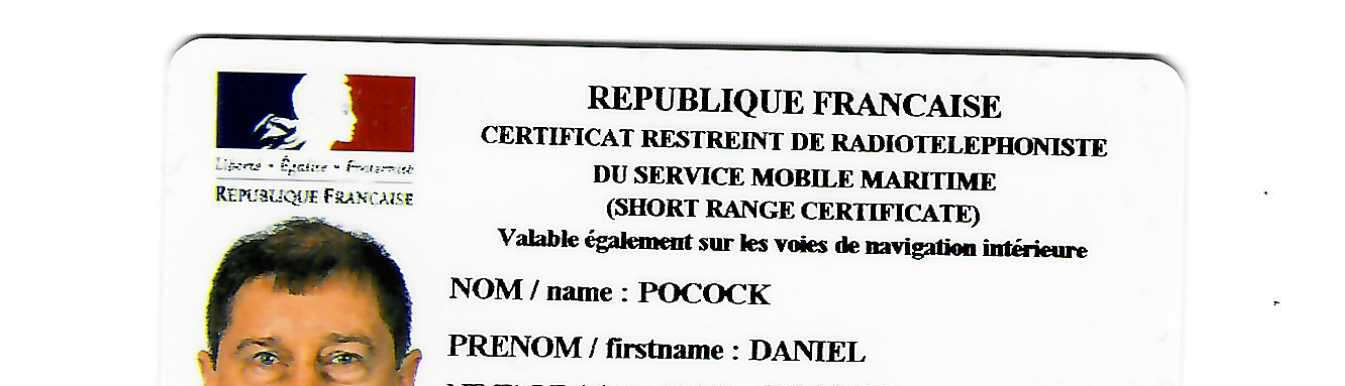

Personally, I completed the marine radio certificate (SRC / VHF) exam in France. So I'm qualified to relay mayday calls in more than one language. The Optus brand is starting to look like Titanic.

One of the questions on my mind after reviewing the public reports about the Optus crisis: is there anybody in senior management who has prior experience in law enforcement or first aid management? Do the regulations in Australia require the telcoms companies to hire people with suitable field experience before operating an emergency call center? These people have life experience that can be very helpful when the culture of the organization is unable to escalate an issue of this nature in the correct manner.

In the financial services industry, state regulators take a keen interest in the structure of the firms and ensuring essential skills exist in the senior management team. Likewise, in the management of telecoms, the state can insist on periodic audits of these firms to ensure they have the right facilities and the right skills to deliver vital services. If the state isn't doing the necessary audits then they have to share the blame with the CEO.

Please see the chronological history of how the Debian harassment and abuse culture evolved.